IMAGE: 800 East Family photo by Ray Herbert aka Panorama Ray, Atlanta; April 1995

Featured on Common Ground

By Ed Woodham

12/9/19

Because libraries have been a refuge for me since childhood, I’ve always thought that if I hadn’t become an artist I would have been a librarian. Following this interest, I’ve become captivated by archives, how they represent and misrepresent us at a marked period. Regardless of their size, archives often fail to include the nuances of our diversity. Or, more egregiously, these annals of time omit nuances as if they didn’t exist. During a recent residency at the MacDowell Colony, for example, I had an opportunity to meet an artist who was exploring the Smithsonian archives. She was searching this vast, seemingly absolute, collection for archival records for specific established female artists whom she greatly admired — yet documentation of their practice was nowhere to be found.

It is here, in the continuum of significance and nuance that my own chronicles began. In the late ’80s, I watched the East Village arts scene, which included many of my friends, flourish then fizzle because of the devastating effects of the AIDS crisis. I had to get out, I decided, and try to save what was left of me and my will power. So, in 1988 after eight years of sexual and creative sanctuary, I fled New York City, and returned to my hometown, Atlanta, Georgia. But during my time in New York, where I had been a manager at the storied Life Café on Avenue B and a regular at the Pyramid Club, Danceteria, The Mudd Club, AREA, Paradise Garage, and the Bronx Ballroom scene, I had watched independent arts spaces wiggle to life from the cracks in the concrete: Club 57, ABC No Rio, Performance Space 122, 8 BC, LaMaMa Theater, The Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Mabou Mines, CBGBs, and so many more. I took this inspiration to Atlanta just as RuPaul, Lady Bunny, Larry Tee, Lahoma Van Zandt, Flloyd, and others were relocating to New York. Soon, they would dominate the nightlife scene.

From 1990 to 1997, a varied collective of multidisciplinary artists — myself included — created 800 East, a warehouse performance and exhibition space with accompanying studios named after its address, in downtown Atlanta. This was before developers started the now prevalent gentrification of downtown areas, at a time when cities across the United States were confronting the crack epidemic and its effect on urban communities. It was also the era when artists could find affordable living and studio spaces without seeming like a potential threat or an omen of displacement to the communities who had lived there for generations.

800 East made its mark during this time of artistic equality. 800 East’s gallery was a cinderblock warehouse that was cold in the winter (heated by a DIY steel-drum woodstove) and very hot in the summer (cooled by lifting up the giant rolling gate and positioning industrial fans throughout the space). In its heyday, the warehouse had housed a construction company. But by the time we acquired the building, it was a neglected property caught in an inheritance dispute. On the same five-acre property was a building I christened “Bauhaus Shotgun,” because its straight-shot construction between the front and back door, with squared-off studios on each side of the long corridor. The property was located in what is now the Old Fourth Ward. Back then, the area was a kudzu field away from The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library – now completely gentrified, beyond recognition.

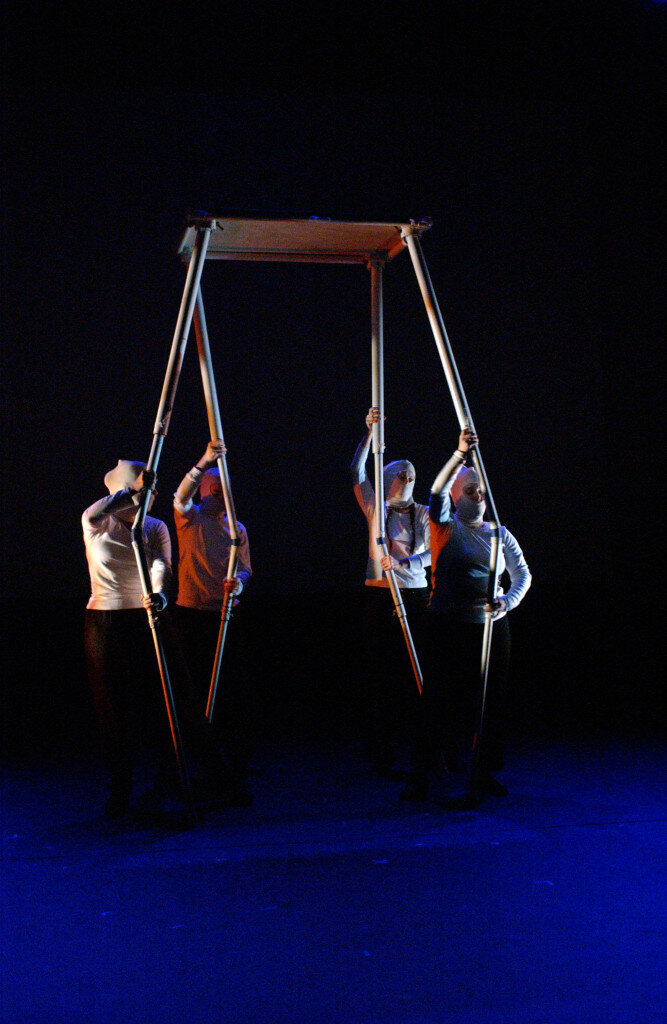

800 East was one of the very few alternative arts spaces in Atlanta in the 90s. It was also a safe haven for racially mixed sexual and artistic ‘others’: queers, bisexuals, lesbians, older creatives, skateboarders, and drag queens. In addition, bands, visual and performance artists, spoken-word artists, fashion designers, playwrights, independent theater companies, puppeteers, and inventors used the space to experiment and to find footing, encouragement, and solidarity. During this time, 800 East developed an ensemble of transdisciplinary artists who worked together for years. We developed, for example, ‘black light walk-through theater’ in which blacklight tubes were hung from monofilament to appear as if floating in midair throughout the 3,000-square-foot warehouse while our Black Light Prom unfolded under its ambiguous glow. Luminescence came from fabrics, paint, and objects rather than a light source. Since we had worked together for so many years, the ensemble — sometimes as many as 100 members — could intuit each other’s hesitation, moods, or need for assistance.

We made these performances, exhibitions, and concerts accessible to everyone. There was sometimes a cover charge — never more than $5 — and even if you didn’t have the money, you were welcomed in with a wave. Our overhead costs were inconceivably low, which made it possible to manage a large-scale, brick-and-mortar art space without much capital. The income we generated by renting the studios was enough to pay the rent, $450 for the entire five-acre property, and we offered the space to as many artists as possible to implement their visions.

Eventually, the bank overseeing the property informed us the family had agreed to settle. They offered us the opportunity to purchase ten acres and the two buildings for $80,000. No one had the money nor could we conceive mustering it up, so we closed the space with a wake and moved on. But I kept meticulous notes, VHS tapes, programs, fliers, invitations, and photos (when no one took photos) and, before returning to New York, I took them in boxes to my parents’ home in McDonough, Georgia, where they were stored on the shelves in the basement.

In 2014, a former 800 East ensemble member, Michael Kilburn — now Dr. Kilburn, Professor of Politics and International Studies at Endicott College, Beverly, Massachusetts — began, with the support of his college, interviewing past 800 East regulars. Michael had previously written a paper on 800 East aesthetics and its artistic movement while completing his doctorate studies at Emory University in Atlanta, and the oral histories he later conducted document in-depth this period of DIY independent and creative agency in Atlanta’s artistic communities. After collecting audio and video interviews for several years and converting more than 50 VHS tapes documenting 800 East events to a digital format, he wrote to [Randy Gue, Curator of Modern Political and Historical Collections at The Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Robert W. Woodruff Library at Emory University.

The letter:

August 1, 2016

Dear Mr. Gue,

I am an Emory University alumnae and read in a recent Emory magazine about your interest in material that “helps complete the cultural puzzle that is the American South.” For the past few years, I have been working with Ed Woodham and other former colleagues to document the activities of 800 East, an experimental visual and performance arts collective that was active in Atlanta throughout the 1990s. The group was extremely prolific, with new exhibits and performances every month for 8 years, as well as off-site initiatives for Mattress Factory shows, First Night Atlanta, Lollapalooza, the High Museum, and others. There is a wealth of archival material: flyers, posters, photographs, video, and original art that may be suitable for your collection. I have also conducted oral histories with many of the principal participants. In retrospect, the activities of 800 East seem like an important piece of the “cultural puzzle” and we would be pleased to contribute materials for archiving, analysis, and possible exhibition. Please let me know if this is of interest. I look forward to your response and possible future collaborations.

Yours, sincerely,

Michael Kilburn (ILA, 2001)

Professor of Politics and International Studies

Endicott College, Beverly, MA

And the reply:

August 1, 2016

Dear Dr. Kilburn,

Good morning. Thank you very much for contacting me about 800 East. I remember going to several shows there.

Yes, the materials are definitely of interest. I would love to add them to the Rose Library’s collections that document art and DIY culture in Atlanta. Is there a good time for me to call you this week so we can discuss your collection?

I am looking forward to learning more about the materials and your project.

Best,

Randy Gue

Curator of Modern Political and Historical Collections

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library

Robert W. Woodruff Library

Emory University

+++

On Tuesday, November 8, 2016, Randy picked up the boxes from my parents’ house. The Robert W. Woodruff Library acquired the 800 East archives, which were to be organized, electronically scanned, and made available to the public on request. Within this fortuitous library-contained history of 800 East is the origins of Art in Odd Places (AiOP), a grassroots project fueled by the idealism, good will, and inventiveness of those who participate. While at 800 East, I led a group of artists in the creation of AiOP to encourage local participation in the Cultural Olympiad hosted during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. In 2005, after moving back to New York City, I reimagined this first Atlanta-based AiOP as a response to the paradigm espoused by the Home Land Security and Patriot Acts that inevitably led to the disappearance of public space and civil liberties in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks.

Since 2005, AiOP has produced a yearly New York City festival where the visual and performance arts are interwoven into the everyday life of 14th Street in Manhattan. Each festival is based around a single focus or theme, always one word: Pedestrian, Sign, Chance, Model, Free, Race, Body, Invisible, and others. After each iteration, I have brought ephemera and artworks from the event to the tiny Brooklyn storage unit that houses the AiOP archives; each year, space in the unit gets tighter.

Since 2012, the festival has also traveled to explore other civic sites in the United States: Los Angeles, California; Greensboro, North Carolina; Beverly, Massachusetts; Indianapolis, Indiana; Orlando, Florida; and abroad in Sydney, Australia and St. Petersburg, Russia. Each of these iterations also produce a box or two of collectibles from the respective explorations of the public sphere.

As I moved into my silver years, I began to wonder what’s going to become of these archives in the future as well as how they could more clearly represent the mission, the accumulated experiences, and the hundreds of artists involved in the immense collaborative effort of AiOP.

Then came this letter:

May 1, 2012

Congratulations! We are pleased to include Art in Odd Places in Spontaneous Interventions: Design Actions for the Common Good, the official U.S. presentation at the 13th International Venice Architecture Biennale (August 29 – November 25, 2012). We received over 450 project submissions and it took us longer than we thought it would to narrow the selection, so apologies for the late notification and the short time frame to turn around this request for materials. Your project will be presented as part of an archive of actionable strategies to improve the public urban realm. Our exhibition of realized interventions in U.S. cities will be accompanied by a full online archive of projects as well as a catalogue/monograph issue of Architect magazine.

Sincerely,

The Institute for Urban Design

+++

On October 28, 2012, Hurricane Sandy flooded my Gowanus, Brooklyn neighborhood. My building’s basement, where I stored archival materials, including the records related to AiOP, was completely underwater. More tragic still, I had just returned earlier that day from my first visit to Atlanta since my mom’s death.

After Sandy struck, I lived in a friend’s apartment for a month while the electrical and gas were restored in my building. During that time of transience, I made a vow to restore the AiOP archives, attempting to replace what had been destroyed.

In 2014, Spontaneous Interventions, housed in building 403 of Governors Island’s Colonels Row, offered AiOP the opportunity to share its history. Curated by longtime AiOP Curatorial Manager Claire Demere, the exhibition, Art in Odd Places: The Artifacts, was a retrospective that examined AiOP through its ephemera, organizers, and contributing artists along with an installation of assorted objects from past festivals. Over two weeks, along with support of past curators and artists, I held panels and workshops reviewing AiOP’s history and influence. This opportunity allowed me to update and collect memorabilia lost to Sandy, replenishing the AiOP archives.

The 2015 edition of Art in Odd Places: RECALL celebrated the festival’s odd-numbered milestone anniversary — 11 years — with a survey of its first ten years. Curators Sara Reisman and Kendal Henry consulted with AiOP’s past curators to establish an understanding of the festival’s history on 14th Street. Of the more than 500 artists who have participated in AiOP’s New York-iterations, 47 past artists were invited to reprise past artworks or present new projects. Following the festival, the now-defunct Lodge Gallery hosted an exhibition that featured a selection of artworks by artists participating in RECALL, which was accompanied by a publicly accessible AIOP archive.

In 2019, as I place another few boxes into the already overflowing storage unit and continue to develop a how-to manual so that others can follow AiOP’s model, I find myself once again pondering the fate of the rich history. Where, for instance, will the archive be stored, shared, and sustained?

It’s also becoming clear that the vast electronic AiOP archive, which includes email exchanges, documents, spreadsheets, evolving templates, designs, invitations, and program guides, is equally essential to telling the many stories of AiOP. For this reason and many others, it is not only important, but imperative, that the AiOP archives represent the full range of experiences and encounters of the hundreds of artists, curators, staff, and festivalgoers who have participated in the project. To neglect the many inspiring and perhaps not-so-subtle nuances of AiOP is to deny its timeless, yet systematic, beauty.

+++

+++

Some links to 800 East videos

6¢, Carnival of the ¢s

Create the Opportunity

Row the Boat

Ed Woodham has been active in community art, education, and civic interventions across media and culture for over thirty-five years. A visual and performance artist, curator, and educator, Woodham employs humor, irony, subtle detournement, and a striking visual style in order to encourage greater consideration of – and provoke deeper critical engagement with – the urban environment. Woodham created Art in Odd Places (AiOP) to present visual and performance art to celebrate the importance of public spaces in New York City and beyond. Art in Odd Places has been produced in the United States: Los Angeles, California; Greensboro, North Carolina; Beverly, Massachusetts; Indianapolis, Indiana; Orlando, Florida; and abroad in Sydney, Australia and St. Petersburg, Russia. AiOP was selected as a representative in the U.S. Pavilion, Spontaneous Interventions: Design Actions for the Common Good at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2012. Woodham teaches art to children 1-4 years old at NYU Early Education Centers and to children 6-12 years old in art programs throughout NYC. He also teaches workshops in politically based public performances at NYU Hemispheric Institute for EmergeNYC and at School of Visual Arts for City as Site: Performance and Social Intervention. In 2017-18, he was an artist-in-residence at the Department of Art, University of Virginia in Charlottesville. In 2019, Woodham was a MacDowell Fellow and an artist in resident working with the City of West Hollywood, California.

Furusho, “a queer, mixed race weirdo art kid from the cookie-cutter suburbs,” says, “I was bullied, harassed, and abused by my peers because I didn’t fit into what “normal” was supposed to mean.”

Furusho, “a queer, mixed race weirdo art kid from the cookie-cutter suburbs,” says, “I was bullied, harassed, and abused by my peers because I didn’t fit into what “normal” was supposed to mean.”